by Cheryl Bonacci

The first time the Harold Robinson Foundation brought students from South L.A. to the overnight camp in the Angeles National Forest, it sparked an idea that somehow the experience of camp might be able to play a role in helping to break the school to prison pipeline. It began a journey worth exploring. The how-to do that needed to be figured out, but the seed had been planted.

Harold Robinson Foundation partners with A.R.C. an organization focused on reforming the criminal justice system

It was when I was the Program Director with The Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC) (a support and advocacy organization committed to helping formerly incarcerated women and men through reentry and advocating for criminal justice reform), and met Jeff Robinson and Joyce Hyser Robinson in 2013, that the lightbulb lit up for all of us. We decided to hold our annual retreat at the camp facility in 2014 and together we knew there was a partnership to be developed between ARC and HRF. ARC brought on retreat 100 young men and women who come from the same communities, or similar to Camp Ubuntu (CU) campers, and the reaction to the environment and opportunities was very much the same: laughter as the primary agenda and a brave space to let down some of the guards that had helped them navigate the challenges of their youth. Our ARC members were once just like their campers. Our members knew the unspoken pain and trauma HRF campers struggled to share. As an organization that works with people who come from a shared lived experience as CU campers, the members of ARC had a unique perspective that no one in HRF leadership had. ARC works with people who are currently incarcerated and/or who recently returned home to the community from incarceration. People of color who had contact with the criminal justice system and/or violence as a youth. We recognized that ARC members were able to connect with our campers in a way that was more powerful and impactful than anything we had created. ARC members who began working with us often commented that if they had had a Camp Ubuntu when they were growing up, they may not have taken the path they did. Through our partnership, we deepened the work that each of our organizations was doing; helping those who have caused harm to heal by paying it forward and guiding our next generation to the brave spaces of Camp Ubuntu and Camp Ubuntu Watts with people who had a shared lived experience, where they could see themselves in a new light and develop skills for a better future.

The Harold Robinson Foundation believes every child needs to be seen, listened to and valued.

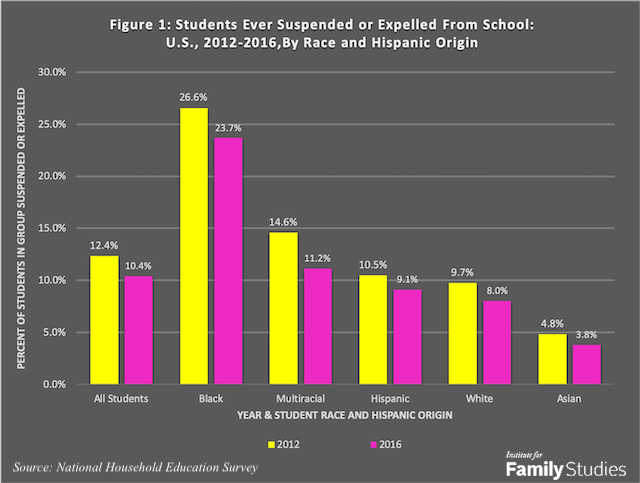

This camp is the space where our work can help interrupt the pipeline that finds our students in under-resourced communities three times more likely to be suspended or expelled and ultimately dropping out of school. The space where creative play helps children learn positive social skills and exercise plays a critical role in academic success. So we did our homework and validated what we know to be true as parents who were once children ourselves, that every child needs to be seen, listened to and valued for them to be empowered to reach their greatest potential. Raising a child whose life had been filled with both, I took for granted the enormous impact creativity and recreation played in his development.

Recognizing how systemic racism feeds the school to prison pipeline

We have a history in our country founded in racism and racially imbalanced systems. We have denied that it has existed, implemented lip service policies and changes that have given the appearance of change and evolution, and turned a blind eye to our most marginalized communities. As long as “they” were NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) and our children had access to quality education, safe playgrounds, and the potential to reach their greatest potential, we didn’t see the problem or simply didn’t care about the problem. Generations pass and the baby steps we have made cannot topple the system that was doing exactly what it was designed to do; ensure that people of color did not have equal opportunities and access. The result has been generations of children stepping out into the world in elementary school wanting to learn how to read and add, but find they are instead destined to go to prison: the school to prison pipeline.

The school to prison pipeline is, in simple terms, the system that has been designed to criminalize children, putting them on a pathway to continued police interaction and a criminal record at a young age from which they will have a mountainous battle to climb to separate themselves. The incarceration of children is the antithesis of what every single child needs to reach their greatest potential. If we were only to punish our children, give them a time out or other consequence but never offered them support or guidance on how to change the behavior, they are doomed to repeat it. Yes, a juvenile criminal record ultimately can be expunged at the age of 18, but the emotional, intellectual and physical damage caused to a child each time they are arrested, shamed, demonized, and consistently separated from the only people who have any belief/love for them, begets the belief of unworthiness and defeat. When we feel unworthy, we are more likely to manifest that belief in unhealthy or dangerous behavior.

What do we expect to happen if we continue to tell our children they are intelligent and powerful with unlimited potential?

What do we expect to happen if we continue to tell our children they are stupid, useless and bad?

I began my career in criminal justice reform as a Catholic Chaplain working with youthful offenders: children ages 14-18 who were being tried and convicted as adults in adult court. I watched child after child leave on a County Sheriff’s bus heading to a California state prison for up to Life Without the Possibility of Parole (LWOP). This is virtually a death sentence for a child. As a single mother with a one year old child at the time, I couldn’t help but make comparisons to my son’s experiences as he became the same age as the young people with whom I worked.

At no point during his early, elementary or secondary school years did he go to a school that had police officers or metal detectors or actual juvenile courts on the property. As a child of color, my son definitely experienced what it felt like to be marginalized or feel like an “other,” but we had the means and opportunity to minimize that.

Why the Harold Robinson Foundation focuses on the transition from elementary to middle school

The truly apparent differences between my son’s potential life path and that of my kids in juvenile hall slapped me in the face in middle school. Middle school is hard. It’s funky. Sometimes that was the only advice I could think to give my son when the endless stream of challenges and struggles and frustrations came out of his body and mouth in inappropriate behavior. For my son, his challenges were met with teachers and administrators who continued to see him as a developing child, a young human being. To give him consequences while also giving him encouragement and support. At the very same time, there were thousands of children in under resourced schools in South L.A. who were getting arrested for being truant because the campus LAPD officer saw them arriving at school for the second period where the policy was that if you are not present for the first period, you are considered truant. These children are handcuffed and taken to juvenile hall – separated from their family, teachers and community. No one ever asked them why they were late to school. No one asked if they were hungry or safe.

We treat children differently depending on the community they live in and the color of their skin.

We ignore their needs and cries for help because they’re not our biological children. At least until their unaddressed pain and trauma turn outward and they hurt someone else…then, we want to throw them away because ‘they should have known the difference between right and wrong’ and now they must be punished and criminalized. What we fail to recognize is that if we ask any one of these children who are incarcerated about their life and childhood (and I have asked many) we discover that their childhood has been riddled with punishment. Their neighborhood isn’t safe, their school is under-resourced and their parks and playgrounds are deplorable if they exist at all.

Over the years,the Harold Robinson Foundation has strengthened our programs implementing social-emotional learning tools and listening to our best experts, our campers. We want to do our part to help make communities safer and break the cycles of inequity. We believe that together we can work toward eliminating the school to prison pipeline. However, until we create a public school system that provides equal, quality education for ALL of our children, remove police officers from school campuses replacing them with social workers and trauma informed credible messengers and provide critical creative, empowering, inspiring opportunities for ALL of our children to learn and grow toward their greatest potential, we will have a school to prison pipeline.