by Joyce Hyser Robinson

Understanding Social-Emotional Education

Social-emotional education, often referred to as SEL (Social and Emotional Learning), is a holistic approach to learning that recognizes the importance of nurturing emotional intelligence alongside traditional academic skills. It equips students with the ability to recognize and manage their emotions, build positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. For underserved youth who may confront economic disparities, violence, and trauma, SEL is a lifeline to navigate these challenges successfully.

Building Emotional Resilience

One of the most significant advantages of social-emotional education is the cultivation of emotional resilience. Underserved youth often face adversities that can lead to chronic stress and emotional turmoil. SEL provides them with the tools to understand and cope with these emotions, reducing the risk of mental health issues. It helps them develop resilience, enabling them to bounce back from setbacks and confidently face future challenges.

Promoting Positive Relationships

Healthy relationships are the cornerstone of a fulfilling life. Underserved youth can benefit immensely from SEL by learning how to build and maintain positive connections with peers, teachers, and family members. These skills translate to better personal relationships and a more supportive school environment where academic success becomes more attainable.

Enhancing Academic Achievement

It’s no secret that social and emotional well-being can significantly impact academic performance. When underserved youth are equipped with SEL skills, they are better prepared to focus on their studies, manage stress, and make informed decisions. This, in turn, leads to improved academic outcomes, breaking the cycle of underachievement that often plagues disadvantaged communities.

Preparing for the Future

Social-emotional education goes beyond the classroom; it prepares young people for the real world. As they grow into young adults, these skills become invaluable in college, careers, and life in general. The ability to communicate effectively, collaborate with others, and persevere in the face of adversity opens doors to a brighter future.

Closing Thoughts

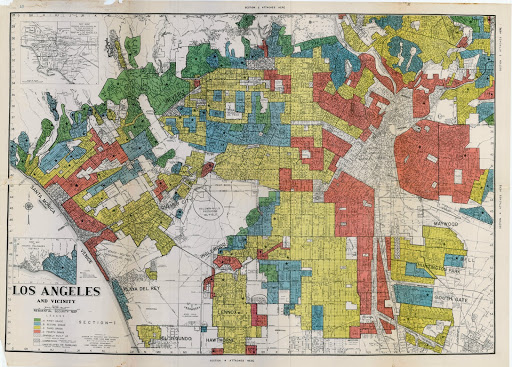

In our cities’ streets and crowded neighborhoods, social-emotional education is not just a luxury but a necessity. It provides a roadmap for our youth to navigate their challenges, develop resilience, and unlock their full potential. By prioritizing SEL, we invest in the future of our marginalized communities, creating a generation of empowered individuals who can break the cycle of adversity and contribute positively to society. It’s time to recognize the importance of social-emotional education for our kids and ensure that every child has access to the tools they need to succeed, not only academically but in all aspects of life.

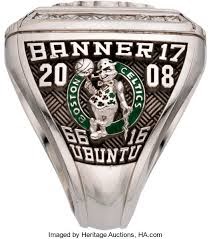

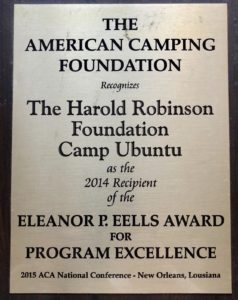

The Role of the Harold Robinson Foundation

The Harold Robinson Foundation stands as a shining example of how social-emotional education can be effectively integrated into the lives of the youth we serve through innovative means. Through our camp programs, such as the flagship “Camp Ubuntu,” we have harnessed the power of experiential learning to instill SEL principles. At Camp Ubuntu, our kids are immersed in nature’s beauty and encouraged to participate in team-building activities, engage in reflective exercises, and learn conflict-resolution skills. By creating a safe and supportive environment where campers can express themselves and build positive relationships, the Harold Robinson Foundation nurtures these young individuals’ social and emotional growth. They emerge from these camp experiences with cherished memories and equipped with a robust set of SEL skills that will serve them well throughout their lives. The Foundation’s approach demonstrates that social-emotional education can be integrated into various contexts, including outdoor experiences, to make a lasting impact on the lives of our South LA youth.