by Joyce Hyser Robinson & Amelia Williamson

1. Language Matters

The Harold Robinson Foundation has joined many others in making a conscious effort to humanize our language and retire euphemisms like inner-city, inner-city children, and underprivileged. It can be unintentional and out of habit, but we all need to be more intentional about the words we use—language matters. We recognize language has the power to cause harm, particularly in the struggle for equitable systems and industries. How can we truly establish equity when we are always seeking to establish an “other.” Language has been used throughout our history to divide communities and infer a sense of someone or some communities being ‘less than’ others. Inner-city, underprivileged, minority and poor are a few words no longer used by many organizations because it speaks to circumstances and not who we are as humans.

2. Not all disadvantaged communities are in the inner-city.

Although it may be factual that some disinvested communities are within the inner-city, not all, and perhaps even most of them are not. Downtown/Inner-City/Center City neighborhoods are thriving and have become increasingly wealthy, displacing many long-time residents to more suburban and rural areas. For instance, Watts, the community we serve, has been commonly referred to as an “inner-city” neighborhood. But Watts is about 13 miles from downtown Los Angeles. For context, so is Beverly Hills.

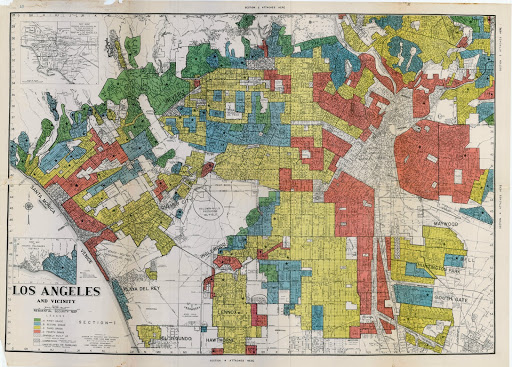

These are stereotypes, and they evoke racial identification based on where one might reside and gives no historical reference to how and why they exist, which brings us to redlining.

3. Terms like “inner-city” propagate historical biases and institutional racism.

“Redlining, a process by which banks and other institutions refuse to offer mortgages or offer worse rates to customers in certain neighborhoods based on their racial and ethnic composition, is one of the clearest examples of institutionalized racism in the history of the United States. Although the practice was formally outlawed in 1968 with the passage of the Fair Housing Act, it continues in various forms to this day.” https://www.thoughtco.com/redlining-definition-4157858

Considering homeownership has been how most American families have generated familial wealth, black people, for the most part, were denied that opportunity. Their communities lacked investment, and they were left to die on the proverbial vine.

One interesting fact about Watts is that from the 1920s to the late 1950s, Watts was considered a diverse, middle-class suburb. The public housing developments, which later became notorious for gang violence, were built by the city during WW11 to accommodate both black and white migrants coming from the southern states for work. It wasn’t until white flight took hold in the late 1950s and early 1960s when whites started moving out to neighborhoods that did not allow for black settlement when all that changed. When Watts became a redlined city, not only did private investment dry up, but the city began its disinvestment from the community. Residents could not get federally backed home loans or any type of home improvement loan. Watts, like many redlined neighborhoods, fell into disrepair and poverty brought on by these racist policies. Predominantly black communities became synonymous with crime due to the policies that set them up for failure.

Harold Robinson Foundation is doing its part to change the narrative.

Sixty years later, we are still marginalizing, dehumanizing, and “othering” our most vulnerable resident – it has to stop. The elevation in social discord we are experiencing as a country has put a spotlight on our collective failure in the way we see and treat each other. Over the past decades, the social justice movement has been working to change policy and the language we use in addressing the issues we face together. Language can have a negative impact on our perception of one another, furthering the divides and implanting a sense of ‘us and them. The Harold Robinson Foundation chooses our words mindful of the importance of empowering people, breaking down the barriers that separate us, and addressing the historic disinvestment of communities that began with redlining. Change happens from the bottom up. It is up to us as an organization that works in Los Angeles’ under-served neighborhoods to do our part to make that change happen. It takes all of us working together to make a difference. That is what we at the Harold Robinson Foundation call working in the spirit of UBUNTU.